“When you think about spacecraft, you may not have considered that they are the world’s most tightly controlled environmental enclosures, the ultimate heavy-machinery operator cab.”

Download the Print version: NASA Spacecraft: Learning from the Ultimate Operator Enclosures [PDF]

Similarities between Spacecraft and Machine Operator Cabs

Heavy-machinery operator cabs are considered “environmental enclosures” as they provide a controlled habitat for the operators while working, with engineering controls designed to protect them from harm. Some are obvious, such as roll-over protection structures (ROPS) and fall-on protection structures (FOPS), but other threats, such as poor air quality, are less noticeable. Engineering controls that assure good air quality include precleaning and filtering the air entering the cab and positively pressurizing the cab above ambient pressure so clean air is leaking out rather than contaminated air leaking in.

When you think about spacecraft, you may not have considered that they are the world’s most tightly controlled environmental enclosures, the ultimate heavy-machinery operator cab. Designed to protect the astronauts from the rigors of space travel, they are completely sealed and positively pressured, and the utmost attention is given to air quality, including the risks associated with carbon dioxide buildup, addressed in the ISO 23875 Cab Air Quality Standard, which can happen quickly when the operator is exhaling into a small, enclosed space.

About Respiration and Carbon Dioxide (CO2)

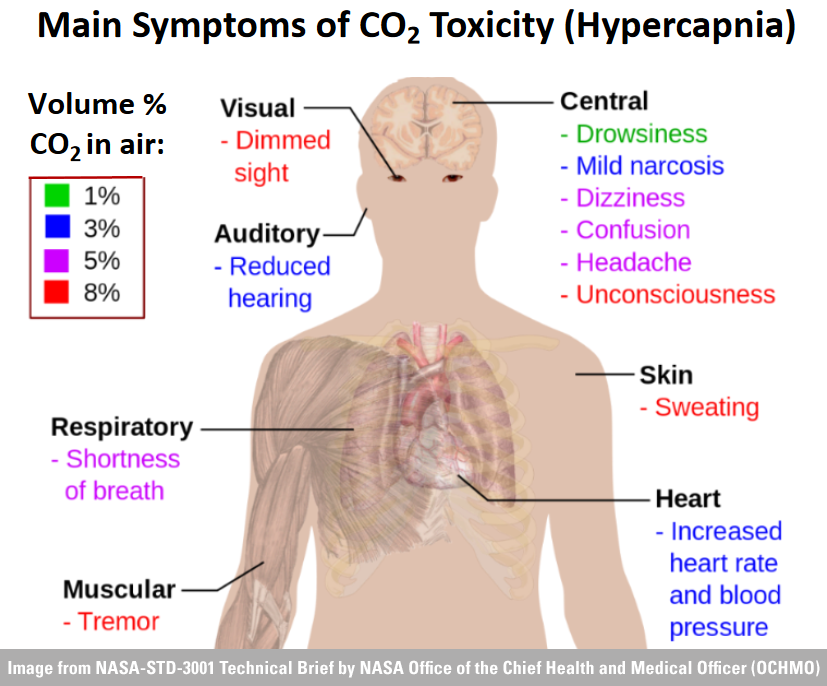

NASA-STD-3001 Technical Brief on Carbon Dioxide (CO2), Rev A, from the NASA Office of the Chief Health and Medical Officer (OCHMO), covers the effects on astronauts from breathing too much CO2:

| “On Earth, our Carbon Dioxide (CO2) levels are managed by our lungs and environment. Our lungs collect vital oxygen (O2) through inhalation, circulate O2 throughout our body and to vital organs via bloodstream, and then upon exhale, release CO2 into the environment. When our respiratory system does not function nominally, either from physical or environmental limits, CO2 can build up in our bodies (hypercapnia) and cause symptoms such as headache, dyspnea, fatigue, and in extreme cases, death.” |

Effects of CO2 Overexposure: Operator Fatigue and Confusion

When testing at various levels of chronic CO2 overexposure from 2.8 to 5 mmHg, symptoms ranged from headaches and fatigue at lower levels, and malaise flushing, nausea, blurred vision, 5th cranial nerve dysesthesia (impairment of the senses, especially touch), and frontal headaches as levels increased.

Machine operators, or occupants of other small environmental enclosures, face the same problems from CO2 buildup as they exhale within a small space. Even at lower concentrations, drowsiness is one of the first effects of too much CO2, and confusion can follow as levels escalate. Without a CO2 monitor in the cab, the operator may be unaware of why they are fatigued, and confusion may lead to poor or delayed decisions. HVAC systems frequently underperform in extreme conditions, such as mines or construction sites. Without a cab air quality system providing only clean, fresh air to the HVAC system, it may fail to introduce adequate oxygen to dilute the CO2 produced by the operator.

When Things Go Wrong

Apollo 13

The NASA brief outlines near-misses that, although caused by other issues, resulted in the dangers associated with CO2 buildup, including the famous Apollo 13 mission in April of 1970. Astronauts used plastic bags, duct tape, and a spacesuit hose to reestablish air filtration, including CO2 removal, sufficient to get them safely back to Earth, all while battling the cognitive impacts of excessive CO2.

Soyuz 23

A lesser-known near-miss occurred with the Soyuz 23 in October of 1976, when mechanical failures caused the cosmonauts to power down systems to conserve battery power. A blizzard forced them to land in freezing lake waters, hampering rescue efforts. The parachute filled with water, pulling the capsule under the surface, shorting out systems, and cutting off all ventilation. When the Soyuz 23 was finally recovered, the crew were alive but unconscious due to high levels of CO2 within the capsule.

Conclusions

While machine operators are not working in the extreme conditions of outer space, they are exposed to similar dangers from excessive CO2 causing hypercapnia (CO2 buildup within our bodies). Environments are often laden with harmful, respirable particulate, leading operators to use the HVAC in recirculation mode, thus accelerating CO2 buildup. In particular, operator fatigue and drowsiness are some of the first signs of too much CO2, which can be followed by microsleeps or even full sleep if CO2 levels continue to rise. Given the types of machinery they are operating, safety incidents, potential loss of equipment, or damage to the site are possible if CO2 is not monitored and managed.

Manage CO2 by Implementing ISO 23875 Cab Air Quality Standard with Sy-Klone’s RESPA®

ISO 23875 is a cab air quality standard that outlines engineering controls and performance requirements to improve air quality in operator cabs, including:

-

- Defined CO2 levels

- Recirculation system efficiency

- Increased filter efficiency requirements

- Defined pressurization requirements

- Real-time cab monitoring

Learn about RESPA Cab Air Quality Systems

Read more about ISO 23875

Print version: NASA Spacecraft: Learning from the Ultimate Operator Enclosures [PDF]